This article by philosophy professor Peter Fosl is part of a series by the Transylvania community on the theme of our academic year: Resilience. As we face the biggest public health crisis in a generation, we’re digging deep to find what it takes to bounce back, to face adversity with both grit and kindness.

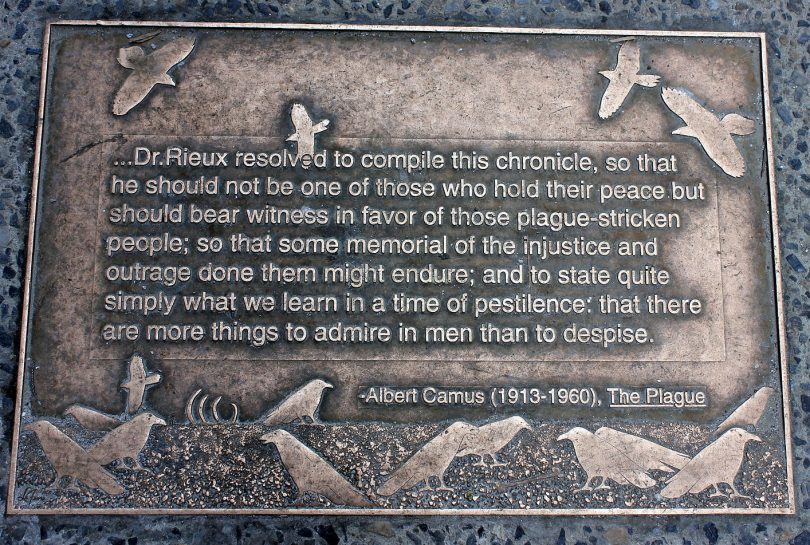

Albert Camus’s 1947 novel, “The Plague,” presents an important touchstone today for obvious reasons. It describes the way its protagonist, Dr. Bernard Rieux, struggles to sustain his humanity in a city under quarantine (Oran, Algeria), while pestilence ravages its population. The situation is as hopeless as it is lethal, since bubonic plague has utterly overwhelmed the capacities available to Rieux and anyone else, really, to put an end to the scourge. But resist he does, as best he can, bravely and compassionately, even in the smallest of gestures — such as venturing out, at great risk to himself, to lance the painful buboes of patients he knows will die. It’s a kind of rebellion, for Camus, against the crushing existential condition we all face.

The end of Camus’s novel, however, speaks to something more particularly linked to the theme of this past year’s remarkable Creative Intelligence program at Transylvania — Resilience. When Oran’s plague tide subsides, the disease does not vanish entirely. A trace of the pathological microbes lingers, ensconced among the tissues of fleas hosted by a few of the city’s elusive rats. Bad things, Camus reminds us, are resilient, too.

Like Camus’s Oran, our society under pandemic siege has exhibited the kind of existential heroism we see in Rieux. I’ve watched mutual aid networks spring up like mushrooms here in Louisville, as neighbors and other people of good will cart food and medicine to those isolated or afflicted by the disease. Attending to the special vulnerabilities of those captive to mass incarceration, folks have also streamed downtown early on Friday mornings to honk horns, holler and wave signs demanding the release of immigrants as well as those accused or convicted of non-violent crimes.

I’ve seen, too, with growing hope the way the world has organized itself with such inspiring unity, determination and financial resources against this virus. As my colleague Zoé Strecker has observed, if we can do so much so quickly in the face of COVID-19, then we can certainly rise to manage the impending threats of climate change. Indeed, we must … and fast.

Of course, the pandemic has also forced us to recognize the commonly under-appreciated but utterly remarkable virtue and fundamental value of the people who every day, plague or no plague, care for the sick and elderly, stock our grocery shelves, put out fires, maintain infrastructure, and in general produce and transport the goods and services without which we would soon wither and perish.

I’ve also noticed, however, something else, something utterly crucial to our future. Persisting among the surreal cruelties to which COVID-19 has subjected us, there still rage plagues of a different kind. Shot through the way we’ve wrestled with COVID-19 are pestilences that have dogged us for a long time now and that threaten devastation on a scale surpassing by orders of magnitude anything we’ve yet seen from today’s pandemic.

Resilient in particular among us are the plagues of human ignorance, irrationality, vice and folly. Racist and classist bigotries have proven utterly durable. Indeed, they flourish. Slow to comprehend the threat before us, too many officials have botched government’s responses to the disease. Misrepresenting the science as well as the politics and economics of the situation, the media have confused more than they’ve clarified. Venerable institutions of science and medicine seem at a loss not only to understand what’s happening but also to marshal the basic resources necessary to confront it. Rattled by selfish panic, masses of fair-weather citizens have turned inward against their communities, hoarding impulsively what they fear losing and producing as a result artificial shortages not only of urgently needed medical equipment but also even toilet paper.

The dominant response to this muddle has been a now familiar plea to “listen to reason” and obey “enlightened” authorities. Historians of ideas like me, however, recognize in that frustrated longing a dreamy nostalgia for the ideals of early modernity — as if there had once been a truly rational era, as if it were possible to make America Enlightened again. More than that, in today’s tangled responses to the novel coronavirus crisis, I’ve discerned another resilient pathology our society suffers — namely, the obstinate and tragic refusal of the humanities and the special gifts that liberal education offers.

The 17th century early modern philosopher René Descartes aspired to establish a science of certainties with a method of such power that it would reverse what to people of his time were the familiar consequences of humanity’s fall from Eden. Descartes’s mathematized deductive science would yield clear knowledge of reality; it would engineer machinery to relieve grinding toil; and it would devise medical therapies that would defeat disease, relieve the pain of childbirth and extend human life indefinitely. The new science and its technologies would, he promised, make us “masters and possessors” of ourselves and of the world. Descartes’ influence remains immense and underwrites an enduring faith among many that with the proper application of reason no problem we face is insurmountable.

Dr. Rieux and those who’ve acquired a liberal education more recently, however, know differently. Students of history are familiar with the profound shortcomings to which individual rulers as well as whole social-political systems are inclined. Historians realize, too, that plagues are nothing new and that we have much to learn about resilience from outbreaks in ancient Egypt, in Lucretius’ Athens, in 14th century Europe, in 17th century England, in 19th century China and India, and across the world during the HIV epidemic of the 1980s.

Those who’ve studied epistemology and logic — especially those like me who’ve attended to the skeptical traditions — understand that epistemic fog is the human condition and that the sciences are best suited not to eliminate doubt but to manage it. We also understand that few beliefs are more charmingly naive than the conviction that science operates independently of politics and economic interest.

Anthropologists such as my colleague Chris Begley know that civilizations cope best with crises of the kind we now face not by dissolving into camps of purportedly rugged individuals but instead by fortifying community and cooperation. Social theorists are familiar with the dreadful implications of social Darwinism and of Thomas Hobbes’ atomized “war of all against all.” They fully realize the brute and calloused power of capital and the resilience of class struggle. Those immersed in the study of religion, no less than students of Freudian psychology, will find it no surprise that the weakened wills, darkened intellects and perverted desires of fallen creatures prove recalcitrant to the rationalistic efforts of engineers and managerial consultants to straighten them out.

Questions about who should and who should not be afforded respirators when the need for them outstrips the number available cannot be answered by virology. Biology cannot determine when the economy should reopen much less whether or not churches should be shuttered over Easter. Epidemiology cannot weigh the costs of stifling the economy, our educational and cultural institutions and our civil liberties against the benefits of flattening the pandemic infection curve. And figuring out how most fairly to distribute federal stimulus funds is not within the wheelhouse of biochemistry.

The findings of scientific inquiry, both natural and social, are crucial to be sure; but the crisis we face also poses questions of a different order. Those questions are matters of morality, justice, goodness, sanctity, human dignity and value — that is, they are the stuff of philosophy, political theory, religion, history, literature and the arts. It troubles me, therefore, that our public conversations about the challenges we face have turned again and again to scientists, to journalists, to celebrity pundits, to business leaders and to political authorities but have rarely called upon medical ethicists, religious thinkers, artists, historians, poets, epistemologists or philosophers of science.

By my lights, our chances for acquiring the right kind of resilience will improve when we attend more to the deliberative and reflective capacities of the arts and humanities. Resilience means more than successfully passing on our DNA, more than merely surviving and more than surviving with money in our pockets. Our best shot at rendering what is fine and good in the world resilient as we move through the arduous gauntlet into which this pandemic has driven us lies in large measure with the widespread adoption of what we do here at Transylvania every day. It lies with liberal education. As it was with Dr. Rieux, our prospects are daunting, but in that struggle there is much to be preserved and much to be gained.

About the author: Peter S. Fosl is editor-in-chief of the academic journal Cogent Arts & Humanities; professor of philosophy, program director of Philosophy, Politics, and Economics; and a fellow of the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Edinburgh. His most recent publications include “Hume’s Scepticism” (Edinburgh UP 2020) and “The Philosopher’s Toolkit,” 3rd edition (Wiley 2020).